An art show featuring paintings by the most recognized Missouri artist of the 20th century runs through mid-August in the main gallery at the State Historical Society of Missouri in Ellis Library.

Born in Neosho, Mo., in 1889, Thomas Hart Benton is best known for leading the Regionalist Movement, which emphasized representation at a time when much of the art world was in love with abstraction. Grant Wood, who painted American Gothic, and John Steuard Kurry, known for his murals in the statehouse in Topeka, Kan., are two other artists identified with the movement.

But Regionalism is not realism. The works in the genre tend to be stylized. Many are emotive and make subtle social commentary.

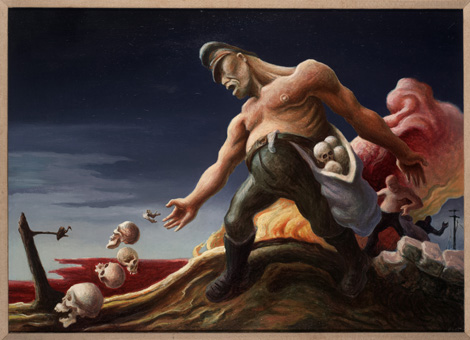

Benton’s eight works in the Mizzou show take representation to a disturbing place. The show focuses on the paintings Benton created in early 1942 in response to America entering World War II. The works, done in egg tempera, show cartoonish figures in a ghoulish world of death and destruction. The style is similar to that of Salvador Dali, but rather than portray dreamy scenes, Benton opts for rendering a nightmare of fear, destruction and paranoia.

“Each one has some image of fire in the background,” said Joan Stack, curator of art collections at the State Historical Society. “It is a hellish world, a hell on earth.”

Benton created the works months after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. The attack jolted Americans to the awareness that the war might be fought, at least in part, in their own back yard.

Fear tends to generate other heated emotions, and for Americans that manifested in hate and racism toward the enemy (the Germans and Japanese were expressing the same toward the Allies). Benton’s 1942 war paintings transmuted these emotions into American propaganda. Stack also includes in the show contemporary editorial cartoons and war posters to show the period’s tumult.

The presentation suggests “the intensity of emotion during the time,” Stack said.

Cover of Time

Benton’s path to the “Year of Peril” paintings, as the gallery show calls them, began when he was a 17-year-old drawing cartoons for The Joplin (Mo.) American. After stints at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Acadèmie Julian in Paris, Benton moved to New York to become a painter. But then he was drafted into the U.S. Navy. Stationed in Norfolk, Va., during World War I, Benton spent many hours making illustrations of shipyard life. Scholars say it was a formative period of his mature style.

After his discharge, Benton returned to New York to concentrate on representational art, and years later he was famous, gracing the cover of Time magazine in 1934.

Benton, at age 46, returned to Missouri in 1935 to create his best-known work, A Social History of Missouri, a series of murals in the House Lounge in the State Capitol. The commission led to his appointment as head of the painting department at the Kansas City Art Institute. His most famous student was Jackson Pollock, a future leader of Abstract Expressionism, which, in about a decade, would make Regionalist art seem passé to the art world.

Benton’s work was never as cut-and-dried as that of some other Midwestern artists. In his 1933 murals portraying Indiana history, he included the Ku Klux Klan, who had become notorious in the state about a decade earlier. His Jefferson City murals depicted scenes of slavery.

If art copies life (or is it the other way around?), it’s not surprising that Benton’s rendering the good, the bad and the ugly suggested his extreme personality. Biographers say Benton could be irascible, and it apparently caught up with him at the art institute in 1941 when he was fired for derogatory comments on race and the institute.Given this, it seems apt that Benton would jump wholeheartedly into some of the ugliness of World War II propaganda.

But as with most of Benton’s art, there’s more going on than first meets the eye.

Calm above the storm

One of the works in the gallery show is titled The Sowers. Benton depicts either a Japanese or German officer sowing skulls, or seeds of death, from his hip-tied bag. In the background, a vulture in silhouette watches from a broken tree as fire explodes from an apocalyptic landscape.

Stack said the work seems almost to foreshadow war atrocities like the Holocaust that came to light months and years later.

Another painting in the show is titled Starry Night, a nod to Vincent van Gogh’s famous work. But where van Gogh sets a spiraling night sky above a tranquil village, Benton takes the opposite approach. Beneath a calm sky, he depicts a horrific scene of a seaman drowning in oily water as flames swoop around him and his ship sinks.

Is Benton employing a technique used by Leo Tolstoy in War and Peace, in which the beauty and detachment of nature is juxtaposed with the horrors of human battle? Is it a commentary on how the ravages of war most often take place in idle settings?

Stack hopes that Benton’s paintings and the gallery exhibits give visitors a sense of the mood that pervaded America in 1942. The uncertainty that gripped the country is hard to imagine today, but it explains the sharpness of the propaganda.

“These were probably more intense to look at during World War II and soon afterward,” Stack said of Benton’s 1942 works. “Now we see them as historical reflections of the mood of the nation. The show is way to let us in to what people at the time were feeling.”