Julija Šukys spent a lot of time in graduate school studying how literature worked. As a doctoral student in comparative literature at the University of Toronto, she learned how to be a critical reader, interpret texts and be a literary scholar. It was only after she earned her doctorate in 2001 that she had a life-altering realization. “I didn’t necessarily want to be the person commenting on books,” Šukys said. “I wanted to be the one writing books.”

Since making the leap from analyzing written works to composing her own, Šukys has published two nonfiction books and is working on her third. An assistant professor of English, Šukys, who just completed her first academic year at MU, teaches and writes creative nonfiction, everything from essays to memoirs to biographies.

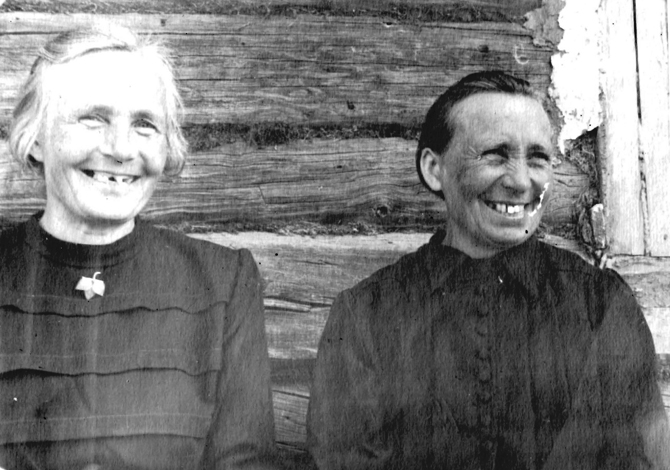

Her current project, tentatively titled In Siberia, is a personal story that begins in 1941 in Lithuania with her grandmother Ona Šukien, who was arrested by the Red Army and deported to a forced labor camp in Siberia. Šukien spent nearly 25 years separated from her husband and three children, including Šukys’ father. When the family finally reunited, they moved to Canada, where Šukys was born and raised.

When Šukys inherited her grandmother’s letters from Siberia, she started digging to see what else she could find. Questions mounted, from what happens to a family when they are separated to how exile and displacement affect a person’s identity to how the experiences of prior generations influence contemporary life. “The work I do is very much a kind of detective work,” said Šukys of research trips to Lithuania and Siberia to sift through letters and archival materials and record oral histories of people in the region where her grandmother lived and worked. “My scholarly training has come in handy for that.”

Šukys’ previous works have had similar themes: dignity, ethics, strength of character. In 2012, she published Epistolophilia, a book about a librarian who was arrested in 1944 and sent to Dachau concentration camp for aiding Jewish prisoners in German-occupied Lithuania. In 2007, she published Silence Is Death, about an Algerian author who was killed in 1993 during conflicts between Islamist extremists and Algeria’s military regime.

In all of Šukys’ stories, she blends the creative with the nonfiction. “You have to work with what you have and learn to cope with what you don’t know,” Šukys said. “One of the challenges is to make something powerful and moving and beautiful and true.”

In the era of the Internet and James Frey (the author of the partly fabricated memoir A Million Little Pieces), the truth is something that she spends a lot of time discussing with her students.

“If we’ve learned anything from nonfiction in the past couple of decades, it’s that you cannot plagiarize, you cannot make stuff up, you cannot blatantly publish material that is erroneous and simply hope no one will notice because they will, and you will be taken to task for it,” Šukys said.

That’s why on her personal website, she has a page for corrections of her work. There are only two, but they kept her up at night. “I decided this was a way of coping with it,” she said. “One of the things that protects you as a writer of nonfiction is vulnerability and honesty. There’s a power in admitting fault, in a weird sort of way.” Many of Šukys’ undergraduate students favor the personal essay where they can explore issues of transition, independence and identity. Her graduate students tend to tackle intellectual questions.

“One of the things we tend to agree on, though, is that the personal is a portal to something bigger. The challenge is how do you marry the big and the small? When there is a marriage of the intellectual and the creative and the personal, that can be really magical.”

— Kelsey Allen

Assistant Professor Julija Šukys stands near the former site of the village of Brovka in Siberia where her grandmother Ona Šukien lived during the first 12 years of her exile from Lithuania. Šukys is writing a book about her grandmother’s plight. Photo courtesy of Julija Šukys.

Ona Šukien, left, and her sister pose outside their house in Siberia circa 1957. Šukien’s arrest by the Red Army led to her being separated from her husband and children for decades. Photo courtesy of Julija Šukys.