Chancellor Bowen Loftin. Photo by Nicholas Benner.

R. Bowen Loftin owns more than 400 bow ties, including black-and-gold variations he’s worn to many university events since starting as MU chancellor Feb. 1.

For decades, his favoring a bow tie over a long tie made him visually distinct among his colleagues. But that’s just surface stuff. What really distinguished him was his personality and accomplishments. Growing up dirt poor in Texas, Loftin found his passion in math and science, received scholarships, became a tenured physics professor at age 33, did pioneering research that included classified NASA projects, and became president of Texas A&M at College Station in 2010. Through it all, he never forgot the lessons of his upbringing.

Loftin, 64, has the ability to relate to people of different ages and backgrounds. During basketball games in Mizzou Arena, he descends to the bleachers to chat with students. Before the start of a recent Faculty Council meeting, he spoke with each press member attending.

His father, Richard Loftin, had the same personable qualities. “He could connect with anyone in a very short time,” Loftin said. “He could find some common element with someone he just met and use that element to build a relationship.”

Loftin is also impressing staff and faculty with his higher-education knowledge. Following a meeting with the chancellor, Faculty Council Chair Craig Roberts marveled at Loftin’s grasp of campus issues.

“He’s already up on so many things,” Roberts said. “You start the sentence, and he’ll finish the paragraph.”

Loftin’s first month as chancellor has been high profile. In response to the case involving freshman swimmer Sasha Menu Courey, Loftin on Feb. 14 announced his appointment of Deputy Chancellor Michael Middleton to examine MU’s relevant rules and practices involving student mental health issues and sexual assault reporting. He fielded questions during the month from local and national media about Michael Sam, a former Tigers football player and soon to be the first openly gay athlete in an NFL draft. And on Feb. 22, Loftin called for inspections of every building owned or leased by MU in response to the death of Columbia firefighter Lt. Bruce Britt at a university-owned apartment complex.

For Loftin, it’s all in a day’s work.

Teacher and Researcher

Richard Bowen Loftin was born June 29, 1949, in Hearne and grew up in Navasota, both pinprick farm communities in eastern Texas. “I grew up riding horses and chasing cows,” he said. His father, who only had a sixth-grade education, worked 10-hour days for the Texas Department of Transportation. His mother, Dorothy, was a homemaker. Both parents wanted their only child to be the first Loftin to go to college.

As a teenager, Loftin was a reader and a farmhand who had a vague notion of becoming a college professor. He excelled at Navasota High School and found a mentor in math teacher Milton Schaefer. Given the socioeconomic status of the family, tuition for Loftin’s education would have been out of reach if not for scholarships. Loftin got two from Texas A&M, 20 miles north of Navasota. The experience led to his career-long championing of university scholarship offerings.

Graduating in three years, Loftin earned his physics degree from A&M in 1970. He received his master’s in 1973 and doctorate in 1975 from Rice University in Houston. By fall 1977, Loftin was an assistant professor at the University of Houston–Downtown. He loved teaching. “I really enjoyed the fact that you could see a light bulb come on, and a student would make [an intellectual] leap,” he said.

Not long into his academic career at Houston, a policy made it mandatory for male professors in the physics department to wear ties. Loftin exploited a loophole in the official language. As his colleagues donned long ties, Loftin wore a bow tie. “Faculty are independent people,” he said, explaining his rebellion. “They resent people telling them what to do.” In time, Loftin discovered advantages to dressing differently (bow ties had been out of fashion since the 1950s). “People remembered who I was. They connected my name to my appearance,” he said. “It was the beginning of my personal branding.”

Loftin flourished at Houston, receiving tenure in 1982 and engaging in cutting-edge research. He directed the NASA/University of Houston Virtual Environments Research Institute and was chair of the computer science department. In the 1990s, Chris Dede was an education and information technology professor at George Mason University who collaborated with Loftin on research projects. “Bowen was a fabulous collaborator,” Dede said. “He was the physicist who brought that expertise to the [education] field.”

The professor also earned teaching awards. “He was not a pomp-and-circumstance type of person,” said Dede, now a professor of learning technologies at Harvard University. “He was a terrific resource for my and his graduate students. He believes what matters is people. He treats people the same, from the graduate student to the Nobel laureate.”

Karin and Bowen Loftin are settling in to The Residence on Francis Quadrangle. Photo by Nicholas Benner.

Administrator and Leader

By the late 1990s, Loftin was juggling a host of teaching, research and administrative duties, including fundraising. At one point, he made a decision to take on more administrative tasks; he could help more students by managing and leading, he reasoned. In 2000, he joined Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Va., where along with teaching he directed the Virginia Modeling, Analysis and Simulation Center.

Then his alma mater called. In May 2005, Loftin became the chief executive officer of Texas A&M’s branch campus in Galveston. He managed 1,600 students and 400 faculty and staff with a fiscal budget of $45 million. He brought stable funding and increased research to Galveston, said Mike McKinney, chancellor of the Texas A&M University System from 2006 to 2011.

But a storm was brewing — literally. On Sept. 13, 2008, Hurricane Ike struck Galveston with 110 mph winds and a 22-foot storm surge. More than 80 people died on Texas’ Gulf Coast. Days before Ike’s landfall, Texas authorities prepared for the storm. But Loftin’s preparation began years earlier. Back in 2005, he and then-A&M President Robert Gates formulated a hurricane evacuation plan for the Galveston campus. Loftin evacuated the campus community to A&M’s College Station campus 145 miles north. Logistically, it was like moving a town, McKinney said. Students resumed classes at College Station and lost only nine class days. All of the students graduated on time. “It was 24/7 to get it done,” Loftin said.

After the waters receded and the skies cleared, Loftin led reconstruction and worked with the state and federal governments on disaster relief. The experience brought the College Station and Galveston faculty and administrators closer, sparking a collaboration that continues today, McKinney said. “He does a whole bunch of things and gives others the credit.” he said.

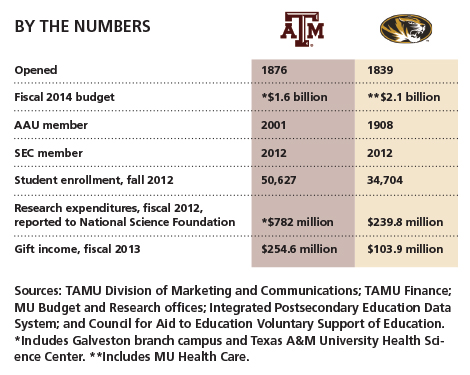

His leadership at Galveston led to his being named interim A&M president June 15, 2009. Eight months later, Loftin became president of A&M, with its $1.3 billion budget and fall 2012 enrollment of 50,627 students. A&M, like Missouri, is a public land-grant research university and a member of the Association of American Universities (AAU) and the Southeastern Conference. Both schools have endured severe cuts to state appropriations for higher education.

Loftin has had a lot of experience balancing budgets. In 2011, Texas sharply cut higher education allocation, and the A&M System board chose not to raise tuition to help make up the deficit. From fiscal 2011 to fiscal 2013, A&M lost about $60 million of its general operating budget, records show. Loftin put together a task force of staff, faculty and students to examine how best to reallocate money. One strategy was giving senior faculty the option of retiring early, and 105 did so, saving A&M $32 million in payroll over the two-year period. The winnowing meant a larger workload for some faculty and loss of many stellar researchers and instructors, but no tenured faculty were laid off, Loftin said. Budgets got balanced.

As for fundraising, A&M kicked off its latest campaign Jan. 1, 2012. Between Sept. 1, 2012, and Aug. 31, 2013, A&M raised $740 million, a record for the university. Loftin now is involved in the One Mizzou fundraising campaign, scheduled to go public in 2015–16. It has a goal of more than $1 billion.

“The key to fundraising, as in most endeavors, is relationships,” Loftin said in a late December 2013 interview. “I have already begun developing relationships with MU alumni and friends.”

From A&M to MU

Last summer, Loftin announced his resignation as A&M president. He wanted to return to teaching and research, or so he thought. On Oct. 1, 2013, Bowen and wife Karin, an associate biosafety officer in A&M’s Office of Research Compliance and Biosafety, bought a home in Bryan, Texas. Meanwhile, Karin had retired. The closing chapters of Loftin’s academic career appeared to have a firm outline.

But days later he was contacted by Storbeck/Pimentel & Associates, an executive search firm hired by the University of Missouri System to help find the successor to Brady J. Deaton. Over the next few weeks, Loftin interviewed by Skype with MU’s 18-member Chancellor Search Committee and spoke in person with UM System President Tim Wolfe and, finally, members of the Board of Curators.

“He was forthright, thoughtful and smart,” said Dean Mills, dean of the School of Journalism and co-chair of the search committee. “Best of all, he seemed to like Mizzou as much as we liked him. And, of course, it didn’t hurt that he wore a black-and-gold bow tie for his video interview.”

Loftin said there aren’t too many schools he would consider at this stage of his career. But MU “fit all the pieces,” he said. He saw an opportunity to affect the lives of thousands of students as a top executive rather than as an A&M professor teaching a few dozen students in a lab. Loftin expects to hold the position at least five years.

Loftin planned to spend much of his first few months building relationships with faculty, staff, alumni and students. A social media dynamo, he personally manages his Twitter and Facebook accounts, and is delving into Instagram. His MU handle is @bowtieger.

As for changes he might make, Loftin said in December it was premature to suggest possibilities. “I’ve got a lot to learn beforehand and want to work from good data,” he said. “Change is good, but it must be done carefully.” Even so, being an outsider, rather than rising through the MU ranks to chancellor, has advantages. “It’s very difficult to be objective when you’ve been somewhere a long time,” he said. “I will see [at MU] what others haven’t seen.”

As was Anne Deaton, Karin Loftin will be involved at MU. “I see my role as supporting Bowen’s goal to promote MU in academics, sports and in the community,” said Karin, who holds a doctorate in biomedical sciences from the University of Texas Health Center at Houston’s Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences. Her personal goals involve promoting cultural exchange internationally and supporting the historic preservation of The Residence on Francis Quadrangle, where the Loftins live.

Asked to describe her husband, she said, “He appears to have endless energy, is a quick study on any topic and has the ability to socialize with everyone.” He is so driven that sometimes he “doesn’t know when to quit and take a rest, although he does try to keep Sunday relatively free from work.”

Looking Forward

During the announcement Dec. 5, 2013, in Reynolds Alumni Center of his being named the 22nd top executive of the University of Missouri, Loftin spoke of his parents, whom he considers role models. Throughout life, he has tried to live by their values. He explained how they mirror MU’s core ideals of respect, responsibility, discovery and excellence.

“You have a lot to be proud of at Mizzou,” he told the hundreds gathered in Reynolds Alumni Center’s Great Room. “It gives me great comfort that I match you and you match me. Karin and I look forward to merging here as your family.”

This article was based on a Loftin profile that appeared in MIZZOU magazine’s Spring 2014 issue.

— Mark Barna