The Pipe Dance and the Tomahawk Dance of the Chippaway Tribe. James Otto Lewis’ sketch was from the treaty negotiations at Prairie du Chien in 1825. Courtesy of the State Historical Society

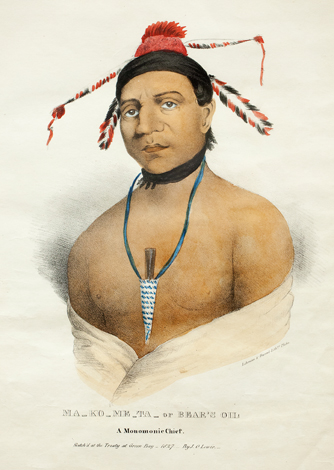

Ma-Ko-Ke-Ta, or Bear’s Oil, a Monomonie Chief. Lewis’ sketch was of the chief at negotiations of the Treaty of Green Bay, 1827. A scalping knife hangs from his neck.

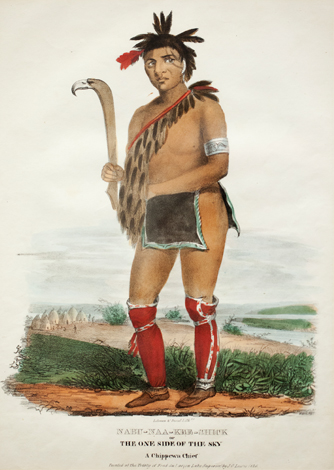

American artist James Otto Lewis documented in drawings several treaty councils in the 1820s and ’30s between Native American chiefs and United States government officials. Dozens of the hand-colored lithographs are on display in the Corridor Gallery of The State Historical Society in Ellis Library through May 31.

Nabu-naa-kee-shick, or The One Side of the Sky, a Chippewa Chief. Lewis’ sketch was of the chief at treaty negotiations at Prairie du Chein, 1825. A U.S. official noted in his log the chief’s incredible physique. In the drawing, the chief holds a war club, its head carved to resemble an eagle.

During this period, the United States was gaining strength militarily and economically, which weakened Native Americans’ negotiating power. Government agents frequently demanded official Indian recognition of U.S. authority, and agents were moving tribes onto reservations.

Ta-Ma-Kake-Toke, or the Woman That Spoke First Chippeway Squaw (Mourning). The woman is mourning the death of her husband in effigy.

In the drawings, the clothing and decorations worn by Native Americans include trade gifts such as peace medals, silver armbands and crescent gorgets. Stereotypes of the natives are also evident. Natives are shown with weapons and wearing animal pelts, including claws and horns, making them appear as savages. In fact, the weapons were mostly ceremonial and the pelts were not common garments.

Some Indians wear native costumes, some wear European dress and some wear both. Their wearing European outfits was often an olive branch to the authorities, suggesting a willingness to cooperate and a friendly gesture.

In 1832, the Indian agent Henry Schoolcraft wrote that an Ojibwa chief wore his native outfit when addressing his people. “To have uttered his speeches [wearing European clothes] would have been associated in the minds of his people with the idea of servility,” Schoolcraft wrote. But when the United States officials were preparing to leave, the chief “bid us farewell dressed in a military frock coat.” The chief knew that the Europeans “would consider it a mark of respect.”