University of Missouri deans, administrators and fundraisers gathered for a half-day summit April 8 in Reynolds Alumni Center to discuss MU’s next comprehensive fundraising campaign, which has a working title of One Mizzou.

Recurring points of discussion included the importance of growing the university’s endowment, finding “big ideas” to attract donors and building relationships over time.

Why now?

Mizzou is in an enviable position, and it’s an ideal time to begin a campaign, said fundraising expert Martin Grenzebach, who served as a consultant on the university’s previous campaign, For All We Call Mizzou, and whose firm, Grenzebach Glier and Associates, conducted research to inform the new campaign.

Mizzou is in an enviable position, and it’s an ideal time to begin a campaign, said fundraising expert Martin Grenzebach, who served as a consultant on the university’s previous campaign, For All We Call Mizzou, and whose firm, Grenzebach Glier and Associates, conducted research to inform the new campaign.

The 2012 Grenzebach Glier and Associates study of nearly 600 current and prospective Mizzou donors revealed that the university has an “overwhelmingly positive image and reputation,” Grenzebach said. Alumni of journalism, medicine and law, in particular, hold their schools in high regard.

“There is a remarkable momentum at this institution that is palpable,” he said, citing the positive forces of stable senior leadership, the success of the last campaign, athletics, enrollment and research.

Roughly 13 percent of philanthropic gifts nationwide go to colleges and universities, Grenzebach said. Many gifts go to foundations, which may ultimately redirect funds to higher education. In 2012 alone, Mizzou received pledges from the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, Sidney Kimmel Foundation and Wallace H. Coulter Foundation amounting to $38.9 million.

Donors understand the need for increased private donations to counter declining state support, Grenzebach said. Historically, donors did not want their money going to what the state used to pay for, such as building classrooms and paying faculty salaries. “It’s less of an issue now,” he said.

However, the institution, schools, colleges and programs must each “have a compelling, urgent story,” Grenzebach said. “Why should someone make a large investment to Mizzou now?”

Endowment

“Great universities in the U.S. have large endowments,” said Chancellor Brady J. Deaton. Endowments provide “stability, a sense of pride, a sense you can tackle tough issues and not have to worry about the rug being pulled out from under your feet the next day.”

“Great universities in the U.S. have large endowments,” said Chancellor Brady J. Deaton. Endowments provide “stability, a sense of pride, a sense you can tackle tough issues and not have to worry about the rug being pulled out from under your feet the next day.”

The university’s endowment can be compared to a savings account from which only the interest is withdrawn each year. By preserving the initial cash balance, an endowment can fund scholarships and programs in perpetuity.

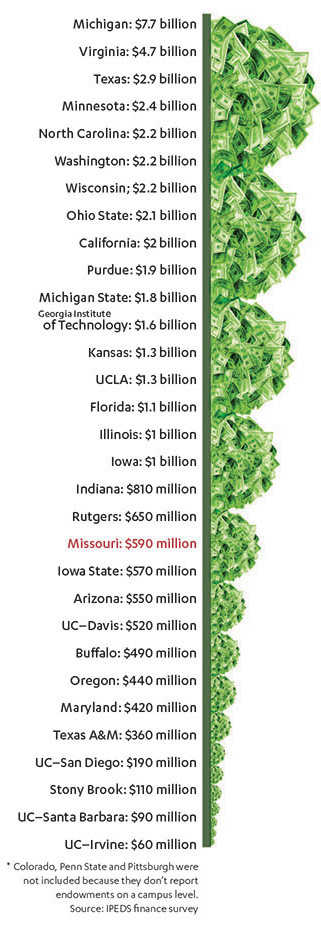

At the start of For All We Call Mizzou, the university’s endowment was $358 million, said Tom Hiles, vice chancellor for advancement. Since 2000, the endowment has grown to $671 million.

But despite this growth, MU’s endowment lags behind its peers.

Universities with larger endowments “have a competitive advantage in recruiting and retaining talented students and faculty,” Hiles said.

Donors often endow new chair or faculty positions in specific academic areas. More than 97 percent of MU’s endowment is restricted for a specific use or program. It is helpful for deans to have flexibility in using the funds.

“I would prefer 10 endowments supporting additional stipends for faculty versus one endowed chair,” said Dean Mills, dean of the School of Journalism. “And I would prefer program endowment to an endowed chair.”

Grenzebach cautioned against over-asking for unrestricted gifts. The minimum amount to create an endowment is $25,000. “Donors who give that amount of money want to have some say in how the money is used,” he said.

Campaigns at institutions such as Mizzou typically generate 3 percent to 4 percent in unrestricted gifts, Grenzebach said. “If you try to drive it much higher, you’re going to end up leaving money on the table.”

‘Big ideas’

Key to Mizzou’s success will be its ability to embrace multiple goals, Grenzebach said. However, public universities do a poor job of communicating goals concisely, he said, and Mizzou is no exception.

The first draft of a case statement — an internal document that outlines the campaign purpose and goals — was criticized for failing to “articulate a unique, defining vision for the university. It includes something for everyone, rather than a plan to strongly advance the institution,” he said.

Donors want to help transform the university, Deaton said. “They are looking for ideas that can help us accomplish that.”

Rob Duncan, vice chancellor of research, stressed the importance of venture capital, citing four successful pharmaceuticals developed at Mizzou: TheraSphere for liver cancer, Quadramet for bone cancer pain, Ceretec for brain imaging and Zegerid for heartburn relief. Three of those discoveries are radiopharmaceuticals developed at MU’s research reactor. Mizzou is one of only five universities nationwide with law, medicine, veterinary medicine and a nuclear research reactor on one campus.

“Donors are beginning to recognize what Missouri can do that nobody in the world can do,” Deaton said. That’s the fundamental core of the Mizzou Advantage, he said. “To bring interdisciplinary work together, to look at these world problems … in ways no one else has done.”

Tom Payne, dean of the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources, cited interdisciplinary orthopedics research by Jimi Cook and nutritional sciences research by Chris Hardin as two examples of collaborating to improve people’s lives.

MU serves humanity at every stage in life, Duncan said. He noted that the university’s largest research grant funds an interdisciplinary collaboration headed by Marilyn Rantz, Curators Professor of Nursing and Institute of Medicine member.

Talk of big ideas continued in a panel discussion moderated by Hiles. Sinclair School of Nursing Dean Judith Miller proposed to build on Rantz’s aging-in-place work to endow an elder tech center. It would involve engineering, human environmental sciences, health professions, veterinary medicine, music and journalism. The big idea for donors, she said, is to help people age safely, with dignity and grace, remaining in their homes and living on their own terms.

Daniel Clay, dean of the College of Education, spoke about his work with the Kansas City public school district, which lost accreditation and was dubbed worst in the nation by U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan. Trying to help the district reach the state threshold was the wrong approach, Clay said. Asking, “How do we make this school district a model for urban reformation in the country?” has generated interest from the Carnegie and Kauffman foundations, he said.

Relationship building

Athletics is “not even close to the most important thing we do at MU,” Intercollegiate Athletics director Mike Alden said. But athletics is the most visible entity, and it can open the door to “launch into all the other initiatives we have at Mizzou.”

Sometimes athletic donors become givers to the academic side of the university. An example is Richard Miller, an entrepreneur and tri-chair of the new campaign cabinet committee.

Miller’s dad, two brothers and grandfather played football at MU, and Miller ran track. Five of Miller’s children graduated from or are currently attending the university.

His family and company gave to athletics for many years. Then, Miller said, he was “discovered” by Bev O’Brien, at the time development director for the College of Arts and Science.

“She made a visit, which was very important,” Miller said. “I saw a face from the University of Missouri.” O’Brien invited Miller to visit the academic side of campus: a first, he said. After several visits, O’Brien asked for $1 million for the mathematics department. Since then, Miller has also donated to business, neuroscience, literature and writing, mathematics education, nursing and athletics.

“I know some people in the academic community think that [athletics and academics] compete,” Miller said. “I’m a good example they do not.”

Although raising money is important, “what we do is not transactional,” Hiles said at the conclusion of the summit. “This is about building deep relationships, and you don’t do that just in passing.”

Ultimately, the campaign’s success will be measured by more than dollars. “At the end of this campaign,” Hiles said, “if we haven’t engaged our alumni in a more dynamic way, if our constituencies don’t feel better about the university, we haven’t achieved success.”

—Angela Dahman

CAMPAIGN TIMELINE

Fall 2011: Recruited campaign planning committee

January 2012: Began quiet phase

Spring 2013: Leadership discussion on case statement

Fall 2013: First meeting of campaign cabinet committee

Fall 2014 / Fall 2015: Public kickoff

Fall 2019 / 2020: Victory celebration

More: MIZZOU magazine's Endowment 101 story on how endowments have benefitted MU students, faculty, facilities and programs since 1888.