Dog owners often think their canines are one-of-a-kind, unable to be duplicated. But that just isn’t so, at least when it comes to body mass and computers.

At MU’s College of Veterinary Medicine, oncologists are using 3-D computer-generated models of cancer-stricken dogs to test-run chemotherapy treatments.

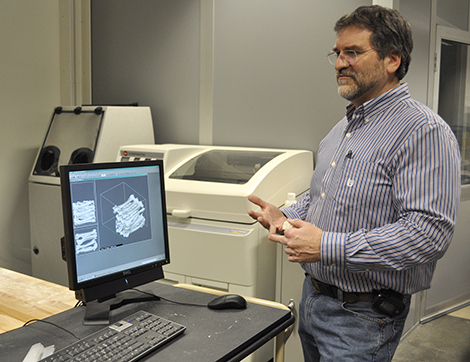

The College of Engineering’s Rapid Prototyping Lab allows users to build functional 3-D models. Engineering students and faculty use the lab’s four prototype machines (better known as 3-D printers) to create inexpensive physical models. They are produced by laying down physical slices (generally plastic or gypsum) one layer at a time until it is fabricated, from the bottom layer up.

Having a life-sized physical model of a dog being treated allows veterinarians to experiment with different doses of radiation and note how much is absorbed into various tissues. This helps determine the lowest effective dose before treatment begins, saving the pooch from receiving more radiation than necessary.

According to Mike Klote, manager of the facility, the potential applications for 3-D printing are nearly endless, as the diversity of client requests illustrate. Among the many models made are that of a cattle breeding device, a prototype of an adjustable high-heeled shoe, and, for University Hospital and Clinics, human spinal replicas, a human aorta and a bronchial system, Klote said.

But it was the veterinary applications that piqued the interest of oncologist Jeffrey Bryan after attending last fall a Mizzou Advantage One Health/One Medicine networking event. Soon after, the lab produced the first canine model — the head of a golden retriever with a cancerous tumor in its nose.

Using a CT scan of the Labrador retriever to get information about the exact density of skin, muscle and bone, the lab created a computer model of the dog’s head. It used the information to create a virtual computer model of the tissues. The file was sent to the prototyping machine, similar to how a Word document would be sent to a standard inkjet printer. Instead of printing letters on a page, however, the prototyping machine prints thin layers, one on top of the other, to create a physical model.

“The therapeutic capabilities are really phenomenal, both in the types of shapes they can make

and the materials they use,” Bryan said. “It’s an amazing process.”

— Tara Ballenger