In 1964, in an unmapped Amazon jungle in southern Venezuela, Napoleon A. Chagnon had his first encounter with the Yanomamö. His academic studies in cultural anthropology led him to expect “noble savages,” a phrase from the 18th-century Enlightenment describing native peoples as nonviolent before contact with modern societies.

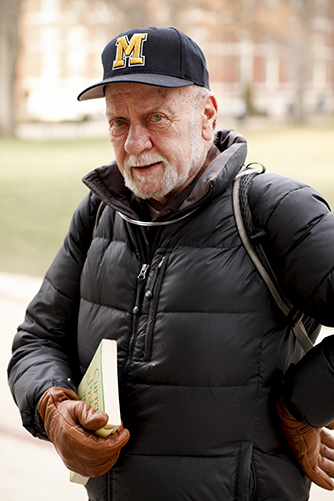

But Chagnon, who joined the MU anthropology department on Jan. 1, quickly understood that the notion, upheld by most anthropologists at the time, was inadequate for field study.

“The virtual noble savage is a construct based on faith,” Chagnon writes is his new book, Noble Savages: My Life Among Two Dangerous Tribes — The Yanomamö and the Anthropologists (Simon and Schuster, 2013), available at most book stores. “In that respect, anthropology has become more like a religion — where major truths are established by faith, not facts.”

In Noble Savages, Chagnon offers a public response to his critics over the years.

And he’s had a number of them. Chagnon’s Yanomamö research made him arguably the most famous anthropologist in America, and also the most controversial. His work chronicled a society where homicide and infanticide were common, and men tested one another relentlessly to exploit psychological and physical weaknesses.

“Their brinkmanship ultimately has an odious sanction behind it,” Chagnon said in a January interview at his home in southeast Columbia. “Penalty, injury, killing.”

His critics said he overplayed Yanomamö violence and too quickly rejected the noble savage idea. He was also wrong to apply evolutionary theory to cultural study. “Most anthropologists were reluctant until recently to assume the academic and philosophical position that human beings have an evolved nature as well as a cultural nature,” he said.

Department rising

Chagnon, whose MU titles are Distinguished Research Professor and Chancellor’s Chair of Excellence, will teach one anthropology course per year, be a faculty and graduate-student adviser, and conduct research. Last year, Chagnon was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. — the fourth current MU faculty member to receive the most prestigious honor in science.

Besides Chagnon joining an already illustrious anthropology faculty, the department welcomed last November Martin Daly, an expert in evolutionary psychology who most recently taught at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada. In 1998, Daly was named a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

Steven Pinker, a psychology professor at Harvard University, considers Daly’s work an important influence in his writing the best-selling The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (Penguin, 2011).

Mark Flinn, an MU professor of anthropology and president of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society, credits Provost Brian Foster for his “special interest in attracting high-profile faculty,” Flinn said.

For his part, Chagnon came to Missouri because of the anthropology department’s reputation, emphasis on evolutionary theory, and how MU departments, colleges and schools work across disciplines in their research, he said.

“We are going to put ourselves on the map,” said Chagnon, who was profiled Feb. 17 in The New York Times Magazine. “Two years from now, we are probably going to be in the top five of evolutionary anthropology departments in the country, maybe the world.”

Robert S. Walker, an MU assistant professor of anthropology, said the

department is getting more than a world-class scholar. “Chagnon brings with him a treasure trove of decades of data from the Yanomamö,” Walker said.

During his final Amazon trips in the late 1980s and 1990s, Chagnon collected mountains of data because he sensed his access to the Yanomamö was drying up. Much of it has not been analyzed. That will change.

“I have brought all that data to Columbia,” Chagnon said.

Controversy in the jungle

Evolutionary biologists say Homo sapiens have not thrown off many motivations of their higher-primate ancestors. One is that males aggressively pursue females for reproductive opportunities, which helps ensure species survival. Chagnon’s Yanomamö studies beginning in the 1960s supported this. He discovered that 30 percent of male deaths were due to fights over women. Typically more than 10 percent of village females had been abducted from other villages during raids (abductions widen the gene pool of a clan village).

“Conflicts over the possession of nubile females have probably been the main reason for fights and killings throughout most of human history,” Chagnon writes.

His biggest broadside to the noble savage sentiment was that the Yanomamö who killed the most Indians in raids had the most wives and offspring, suggesting a Darwinian survival advantage for kinship defense and intense aggression.

In 1995, Chagnon’s fieldwork abruptly ended when Venezuela denied him access to the Yanomamö villages. Chagnon had publicly criticized the Catholic missionaries for, he said, supplying the Yanomamö with shotguns. According to Chagnon, the Catholic Church has a foothold in the Venezuelan government and controls access to the southern Amazon. Because of his criticism, church officials pulled political strings to block him from the region.

Meanwhile, beginning in the mid 1970s, Chagnon was under attack from many anthropologists for his embrace of evolutionary science. He was accused of racism, sexism, biological determinism and cooking his research to square with his preconceived theories. Some said his work supported the American eugenics movement, an effort to improve a society’s gene pool, which stirred up memories of Nazi Germany’s attempt to exterminate the Jews.

“Anyone who suggested an evolved biological nature for humans was considered heretical,” Chagnon said. “People like me were singled out to bear the brunt of their wrath.”

Other scholars accused him of interfering with Yanomamö culture and in 1968 spreading measles through villages. The American Anthropological Association got involved. After years of debates and the formation of a task force, association members in 2005 voted to exonerate Chagnon of any wrongdoing.

Chagnon retired from the University of California–Santa Barbara as an emeritus in 1999. Blocked by Venezuelan officials from Amazon fieldwork, he decided to leave academia. But as years passed, the scientist couldn’t shake the feeling that he had more to offer.

Staring down a killer

Chagnon spent an aggregate of five years with the fierce Yanomamö.

He gave them fish hooks, axes and other items in exchange for information and his presence in villages. He would also sometimes shoot game for them. The Indians understood that if they harmed him, the gifts would stop. “Keep in mind the story about the goose that lays the golden eggs,” Chagnon said, smiling. “If they got rid of the goose, there wouldn’t be any more golden eggs.”

Even so, several times over the years the Indians tried to kill him, Chagnon said.

The anthropologist’s time in the jungle took its toll on his health. The Amazon sun sucked out much of his skin’s collagen, leaving it blotchy and prone to bruising. He endured all kinds of tropical illnesses, including malaria. Symptoms from his illnesses linger. To relieve the stress of the jungle, he took up smoking and didn’t quit for 50 years.

Chagnon is good company, but he has an edge. This no doubt helped him endure the hardships of the rain forest and Indian culture. In his book, Chagnon writes of staring down a headman who had killed 21 people and witnessing astonishing acts of violence. He had close calls with jaguars and an anaconda, which sprang from murky depths to thrust its maw inches from his face.

Yanomamö kindness

As Chagnon makes clear, the Yanomamö are warriors. But they also can be kind and sympathetic. Since villagers were almost all blood related, and they understood strength in numbers, the village Indians helped one another survive sickness and raids. They were noble savages. The book’s title is not simply ironic.

In his book, Chagnon describes a village cremation service in which Yanomamö wailed over the loss of a village headman in a raid. Chagnon retired early to his hammock after the service. Word got around that the anthropologist was mourning. Villagers came to comfort and gently touch him.

Within their creation myth, the Yanomamö are separated from the wild beasts. They understood that they were not like the jungle creatures and pale outsiders — the Western anthropologists, doctors and Christian missionaries who visited them. They were human beings.

Chagnon’s heavy heart that day showed villagers that the white man wearing the strange clothes was not naba, meaning subhuman or savage. He was like the Yanomamö.