Phillip Vinyard is a hard-working assistant manager at University Physicians’ Green Meadows Family Medicine. But at night, he’s a foot-tapping, string-plucking bluegrass musician.

Different worlds? Not so much.

“Creative is creative,” Vinyard said. As an assistant manager, “I’m paid to solve problems, and that comes out in a lot of different ways. Music is also creative, just a different type.”

MU faculty and staff have a variety of hobbies and passions, and for some its music. After a day at their nonmusical day job, they go home to practice music scales, teach music classes or prepare for a public performance in the genre of bluegrass, country, folk, rock ’n’ roll or classical.

For players like Vinyard, musical moonlighting is creatively similar to the day job. For other MU employees, music is an oasis from the day’s intellectual rigor.

Steve Watts is a history professor who specializes in cultural trends. He has published a handful of books, most recently Mr. Playboy: Hugh Hefner and the American Dream. He’s currently working on a biography of Dale Carnegie.

Yet he also loves to rock.

“Something about it is very fulfilling,” he said, “a certain kind of expressive joy.”

Watts helped support himself financially by playing music while an undergraduate in the 1970s. In the mid-1990s he founded Big Muddy, which continues today despite member changes.

The creative process of playing music and book writing is similar, Watts said. “They are two different species of the same creature.”

Big Muddy also includes guitarist Soren Larsen, an assistant professor in the geography department; and keyboardist Heidi Harmelink, a development research analyst in the Office of Development.

Harmelink has been the band’s keyboardist for three years. She’s a classically trained pianist who began playing at age 6. Besides Big Muddy, Harmelink performs in various orchestras and bands for local theater productions.

She said there’s plenty of overlap as a research analyst and keyboardist. Study and creativity bring piano playing and research data alive. “To do data mining in my job you have to be pretty creative,” Harmelink said.

David Silvey, a senior strategic sourcing specialist in Procurement Services, is a folk guitarist and songwriter. He likes nothing better than sitting on his porch strumming his acoustic guitar.

“I play almost every night,” Silvey said. “By 9 or 10 o’clock, the kids are to bed and it’s my time. It’s an escape, a stress reducer.”

Music is also an escape for jazz guitarist Jack Schultz, director of the Bond Life Sciences Center. “It is pleasing and satisfying, but also requires enough concentration to keep my mind away from other issues for a while,” said Schultz, who has played in a number of Columbia jazz bands over the years, including the Jack Schultz Trio.

Schultz has bonded with fellow scientists through music. Years ago, he did research at a field station in a Costa Rican rainforest. Nights typically were spent singing and playing songs with colleagues.

“Those activities certainly cemented relationships among scientists, even if they didn’t change experimental outcomes,” Schultz said.

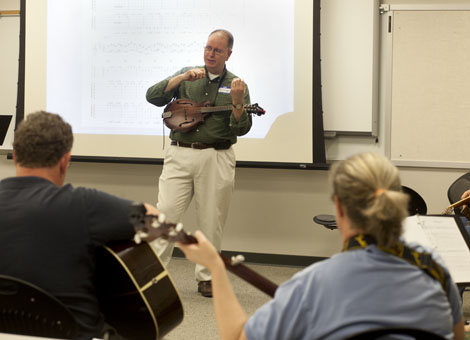

On a recent evening at the Columbia Area Career Center, Vinyard prepared to teach bluegrass to 20 students, variously strumming mandolins, acoustic guitars and banjos.

For decades Vinyard played the cello and performed with college and community orchestras. Five years ago, at age 50, he got the bluegrass bug and took up mandolin.

Playing music at home alone is fine, Vinyard said. But sharing the experience with others should be the goal.

“I want to encourage them to keep going,” Vinyard said of his students, many of whom are bluegrass beginners. “I will consider it a failure on my part if they don’t play with other musicians.”

Vinyard practices what he preaches. He’s become a fixture at local bluegrass jams, where he’ll kick up a foot to signal a song’s end or nod to a fellow jammer to take a solo.

By day, University Physicians assistant manager. By night, mandolin player, sharing the experience of, in his words, “smoking hot bluegrass.”