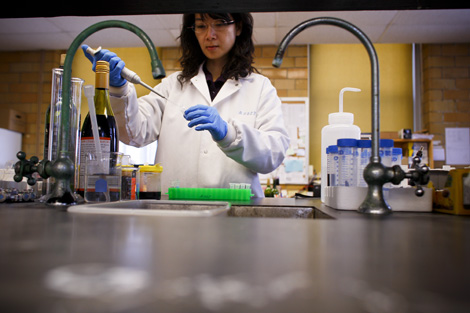

Connie Liu sticks her nose into a long tube attached to a wine machine. She sniffs, jots down the scent on a notepad and checks a computer screen to analyze the scent’s chemical composition.

“This Norton wine smells like wintergreen or mint,” she says, pointing to a chart that measures flavor composition. “It’s the methyl salicylate.”

Liu’s mission is to create a more palatable Norton wine for Missouri’s wineries. Former Gov. Bob Holden declared the Norton grape, sometimes referred to as Cynthiana, the official state grape in 2003 to promote its usage.

Liu works for the Institute for Continental Climate Viticulture and Enology (ICCVE), in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources. The institute incorporates the work of researchers throughout the state.

At MU, enologists, who study wine and wine making, and viticulturists, who study the science and production of grapes, are working to help expand Missouri’s $1.6 billion wine industry using the Norton grape.

“The flavor and the quality of the Norton wines have improved dramatically over the past decade,” said Ingolf Gruen, interim director of ICCVE. “While wine connoisseurs 10 years ago would possibly have spit it out, today’s Norton wines have found a strong following.”

Making grapes sweet

The Norton grape is one of the oldest grape varieties in the United States. In the mid-18th century, Virginian settlers transported the grape to Missouri, where it has thrived in the state’s continental climate.

Noble grapes, such as pinot noir and sauvignon, are too susceptible to Missouri’s humid summers, dry winters and pests. But where it prevails in hardiness, it lacks in sweetness.

Sweet wines are popular in the Missouri wine industry and drive demand.

“Most Americans start out on the sweet side,” said Jim Anderson, executive director of the Missouri Wine and Grape Board. “We have a little bit of a sweet tooth in this country.”

Using pure chemistry, Liu said it’s possible to create a Norton wine without the grapes and the traditional winemaking process.

But she also said the scientifically manufactured beverage would be to wine what Kool-Aid is to fruit juice: It wouldn’t have the taste or nutrients that organically produced wines have.

Liu analyzes how factors from the grape-growing process, such as trellising, sun exposure and climate, affect wine taste. She hopes to find a Norton wine that entices the tastes of sweet-wine drinkers. If people prefer sweet, that’s what vineyards and wineries will sell. Quality, Gruen said, is subjective.

“It doesn’t matter if someone says, ‘Hey, I like this cheap wine,’” Gruen said. “So be it. We’re happy to sell it to you. Eventually it’s all about making profit. You want to sell what people like.”

ICCVE branches out through an MU extension program to train winemakers and help the 400 grape growers and 114 wineries in the state.

Cory Bomgaars, head winemaker at Les Bourgeois Vineyards in Rocheport, Mo., and vice chair of the Missouri Wine and Grape Board, said ICCVE has given local winemakers opportunities.

Les Bourgeois offers an informal internship often occupied by an MU student. The winery also hires several students from the university, which Bomgaars said helps to complement the students’ time in the classroom with the real-world business experience of running a vineyard and winery.

“The pool of students is amazing to us,” Bomgaars said. “We’ve had a long history of having endless talent of interested people come from the University of Missouri.”

Missouri’s global impact on wine

In addition to its modern economic impact, Missouri has left an indelible impression on global wine history.

Waves of settlers moved to Missouri in the mid-19th century and established several vineyards and wineries. The wine industry expanded, and up until 1919, Missouri was second in the country only to New York in terms of wine production.

Missouri also saved the French wine industry from obliteration. Charles V. Riley, Missouri’s first state entomologist and a lecturer at MU, confirmed that a louse called phylloxera was destroying grapevines throughout Europe in the mid-18th century.

He proposed grafting the French grapevines with rootstocks from American grapes.

MU Professor George Hussman collaborated with the state’s grape growers to gather millions of these rootstocks. The solution worked, and two statues in Montpelier, France, commemorate Missouri’s contribution to French wine.

Prohibition ended a robust chapter in Missouri’s wine history. Missouri wines didn’t return until the 1960s, when the Held, Hofherr and Dressel families revitalized it.

The industry has grown significantly since; Anderson said Missouri ranks eighth nationally in wine production and 10th in grape acreage.

“It’s been a great partnership,” Anderson said of working with CAFNR. “We’re working together to solve problems for agribusiness and wineries.”

— Trevor Eischen