Modeling and prototype development are routine components of engineering. The University of Missouri’s College of Engineering is taking advantage of technological advances to establish a lab that offers students experience with the latest in modeling software and prototype equipment.

And by offering for-pay prototyping services to on- and off-campus entities, the college has been able to recover its costs on the equipment and materials, as well as improve its services.

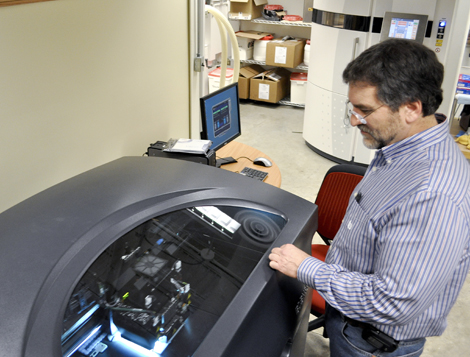

“This business configuration allows us to bring expensive state-of-the-art equipment to the undergraduate program that we normally couldn’t do,” said Mike Klote, engineering lab manager. “We have unique capabilities within engineering that don’t exist in many places, including four rapid prototype machines, each with a slightly different process and a unique function.”

Prototyping technologies work on the principle of additive manufacturing — materials are joined together, layer upon layer, to make three-dimensional objects based on modeling data. Software used to create 3D models, such as Pro-Engineer and the industry standard SolidWorks, are 90 percent of the entire rapid prototype process, according to Klote.

Klote said more than half of the work is done by students working on senior capstone projects and by student competition teams. The captain of MU’s Society of Automotive Engineer’s formula car team was one of two undergraduates hired by Klote last spring to work in the lab. He landed two internships this past summer because of his experience working with modeling and prototyping.

Klote plans to offer a class on the technology beginning in the spring 2012 semester.

In addition to prototypes for engineering faculty research, several projects have been completed for MU entities, such as veterinary medicine, human environmental studies and the biodesign program.

“We made dog leg bones for vet-med students learning pet orthopedics,” Klote said. “That way they don’t have to use real dogs for the training.”

Another campus project involved modeling an ear canal for student surgeons at MU’s School of Medicine. Future models will be coated with a metallic paint. Klote likened it to the game “Operation” because a buzzer will sound when the student surgeon “slips up.”

Microdyne LLC, a St. Joseph start-up with an idea for a novel device for use in the cattle industry, has taken advantage of the prototype labs capabilities.

Company spokesperson Jim Jackson said that 80 percent of all dairy cows are artificially bred. Jackson said the primary indication that a cow has entered the four- to 12-hour window during which she can successfully be bred is that other cows “in sympathy” will mount her. The company’s patented device, affixed just above the cow’s tail, measures these standing mounts, communicating that a cow is “open” with three different signals: an LCD light, an LED light that flashes in a pattern indicating the number of mounts and an audible beep.

The company had MU’s prototype lab develop the plastic casing for the device. A Centralia company developed the circuitry and a Colorado firm fabricated the circuit boards.

The first version of the device, the “TattleTaleTM,” is already on the market. Jackson said the company marketing it is eagerly pressing to test a second version that addresses some problems with the original.

“We’ve worked with companies as far away as Texas,” Klote said. “A new mold to use in a standard manufacturing process can cost $30,000 and you may need only 100 of something like, say a knob. Those parts can be fabricated easily and cheaply using rapid prototyping.”

The original work for Microdyne’s prototype was done on the Objet machine, a polyjet system that uses photopolymer resin. The machine’s inkjet-like heads dribble out the resin, the light passes over to dry cure it and another layer drops down. The fine layers allow for very smooth surfaces and fine details. The machine supports a number of materials providing options for flexibility and color.

The second rendering of Microdyne’s case was completed using another machine, the EOS Formiga. Klote said the rendering needed to be more sturdy and the Formiga’s SLS process uses polyamide, or nylon, which is extremely durable.

SLS stands for selective laser sintering, a process in which a laser melts one-milliliter layers together to form a computer-modeled prototype. “It’s very high resolution and can make super small models. It also has very good thermal characteristics and can make many parts at one time,” Klote said. “It’s like magic.”

A third prototype process uses 3D printing technology. Printer inkjets build up layers of gypsum and when finished, the prototype is removed from the machine and extracted from the loose gypsum. The process is fast and can make full-color, high-resolution models.

A fourth prototype machine, the Dimension Elite, has been added to the lab and is scheduled to be operational soon. The Elite uses fused deposition modeling, a process Klote likened to a hot glue gun, which extrudes a thin thread of thermoplastic and then knits each layer together.

“It doesn’t have the finest resolution, but models are extremely robust. It will be the cheapest of the three plastic processes we offer,” Klote said.

Soon, Klote hopes to add sterolithographic prototyping (SLA) equipment, which uses photo curable resins to rapidly manufacture several parts of different shapes and sizes at the same time.

“The SLA system will be our top-of-the-line machine,” Klote said. “It’s a very expensive game to get into, but our fee-for-service arrangement will hopefully allow us to purchase the system and offer that technology.”

In addition to the lab’s long-standing electronic circuit design and circuit board development abilities, the new technologies now on hand will make the lab a one-stop shop for assisting prototype development.

“We’re open for business,” Klote said. “We just need to get the word out.”

— Janice Wiese-Fales